What I’ve Been Watching: The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957).

Who’s Responsible: David Lean (director); Carl Foreman, Michael Wilson (screenwriters); William Holden, Jack Hawkins, Alec Guinness (stars).

Why I Watched It: SILVER.

Seen It Before? Many times.

Likelihood of Seeing It Again (1-10): 10.

Likelihood the Guys Will Rib Me for Watching It (1-10): 1.

Totally Subjective BOF Rating (1-10): 10.

And? The first, and in my opinion best, of the epics that characterized the second phase of Lean’s directorial career—yes, even surpassing its immediate successor, Lawrence of Arabia (1962), followed by the quintessential doomed romance, Doctor Zhivago (1965), the anomalous and critically panned Ryan’s Daughter (1970), and A Passage to India (1984), made after a long hiatus and thus the only one I saw on its original release. Of course, with Holden and Guinness being among my favorite actors, and WW II being a favorite milieu, this one had more than a slight edge. Learning that author Pierre Boulle also wrote the novel upon which Planet of the Apes (1968) was based didn’t hurt, either.

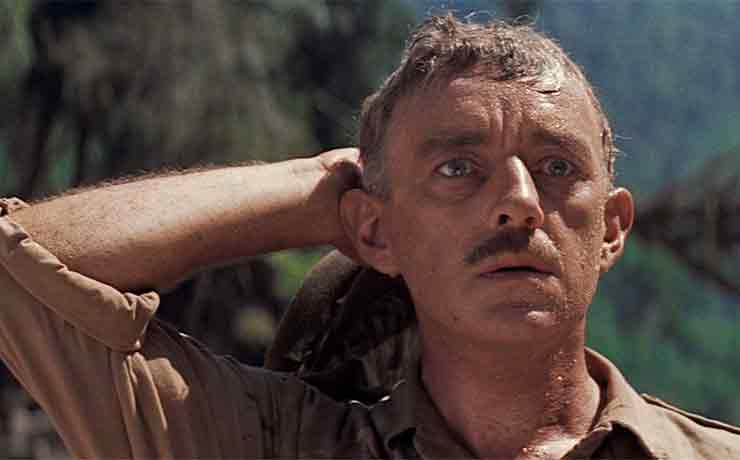

(L-R: Guinness, Holden, Hawkins)

Guinness appeared in all but Ryan’s Daughter, and had also starred in Lean’s Dickens adaptations Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948). The editor of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1938) and Major Barbara (1941), and the Archers’ 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), Lean had ascended to the director’s chair in a fruitful collaboration with actor, playwright, and screenwriter Noël Coward on In Which We Serve (1942), which Coward co-directed, This Happy Breed (1944), Blithe Spirit and Brief Encounter (both 1945). He’d earned Oscar nominations for Brief Encounter, Great Expectations, and Katharine Hepburn’s Summertime (1955).

Lean finally struck Oscar gold when Kwai won Best Picture, Actor (Guinness), Director, Adapted Screenplay (more on that in a moment), Cinematography (Jack Hildyard), Film Editing (Peter Taylor), and Scoring (Malcolm Arnold); Supporting Actor nominee Sessue Hayakawa was the only exception. This being the era of the Blacklist, one of America’s greatest shames, producer Sam Spiegel gave script credit to Boulle, whose award raised some eyebrows because he did not speak English. It was not until 1984 that Foreman and Wilson were awarded their retroactive and, sadly, posthumous Oscars (Foreman died the day after it was announced), and their credit was later rightfully restored to the film itself.

Previously a winner for A Place in the Sun (1951) with Harry Brown, and a nominee for 5 Fingers (1952), Wilson suffered the same indignity with his nominations for Friendly Persuasion (1956) and, with Robert Bolt, Lean’s Lawrence, also subsequently granted. By the time he and Rod Serling adapted Boulle’s La Planète des Singes (both books had been translated by Xan Fielding), Wilson could be credited openly. Foreman, a WW II vet whose work Lean had Wilson rewrite, earned additional screenwriting nominations—and a place in the BOF pantheon—for High Noon (1952), produced by Stanley Kramer, and The Guns of Navarone (1961), a Best Picture nominee that Foreman also produced.

Himself a former POW, Boulle insisted that his novel (whose English-language title uses “over” rather than “on”) was not anti-British, and I agree, although Guinness was among those who did not, initially making him reluctant to accept the role of Colonel Nicholson. Like the bridge itself (above), the script was built on a solid foundation, with the scenarists wisely retaining most of Boulle’s narrative, which opens as Nicholson’s men are put into a POW camp and ordered to construct a railway bridge that will help link Bangkok and Rangoon. While written in the third person, it often adopts the perspective of Major Clipton (James Donald), the medical officer alternately impressed and bemused by the C.O.’s behavior.

Nicholson swiftly engages in a war of wills (above) with his Japanese counterpart, Colonel Saito (Hayakawa, below), who thinks the prisoners will be motivated by his “egalitarian” insistence that the British officers perform manual labor alongside them. Enduring various forms of abuse, Nicholson maintains that this contravenes the Geneva Convention, about which Saito doesn’t give a hoot, but also is counterproductive, since they will work better with their officers supervising them. His life on the line if the work is not completed on time, Saito caves, clearing the way for Nicholson, Captain Reeves (Peter Williams), and Major Hughes (John Boxer) to supervise a proper bridge that will instill pride and raise morale.

Suspense is generated by intercutting these scenes of the bridge’s construction with those of an approaching commando team dedicated to its destruction, sent in by Colonel Green (Andre Morell) of Force 316. Assisted by Siamese partisans, the group consists of Shears (Holden), old hand Warden (Hawkins), and a young, untested Lieutenant Joyce (Geoffrey Horne); so far, so faithful, and the foregoing applies equally to page or screen. But where the scenarists turn a good novel into one of the greatest films of all time—yes, I said it—is by radically transforming Shears from the British leader, a founding member of Force 316, to a reluctant member, a U.S. Navy commander who escaped from the Kwai camp.

Set in 1943 and shot in Ceylon—now Sri Lanka—the film immediately adds elements to enhance this story when we first see Nicholson’s men, finishing a forced march to Camp 16 and defiantly whistling the traditional “Colonel Bogey March” in spite of their tattered appearance. That and Arnold’s orchestral counter-march are heard separately or together throughout; amusingly, I detect echoes of his work here in every movie I’ve subsequently seen that Arnold scored before or after this one. The arrival of the British is observed by Shears, separated from his crewmates when the U.S.S. Houston sank, and an Australian, the uncredited Corporal Weaver, the only two survivors from those who built the camp.

The roles of Nicholson and Shears were intended for, respectively, Charles Laughton and Cary Grant, but it’s tough to imagine anybody better suited than Guinness (billed, believe it or not, below Hawkins, above) and Holden. The latter, in fact, had already won an Oscar for a similar turn in Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17 (1953) as cynical POW Sergeant J.J. Sefton, who will do anything to survive in the camp. The film also brilliantly visualizes Nicholson’s ordeal, having him confined in “The Oven,” a shack made of wood and corrugated metal that is too small even for him to stand up; Clipton tries in vain to get him to compromise while visiting the C.O. there (below), and Nicholson’s release is jubilantly celebrated by his men.

Meanwhile, Weaver and a British lieutenant are killed attempting to escape, as Shears is presumed to be after he is shot and plunges from a cliff into the water, yet he painfully makes his way through the jungle to a sympathetic Siamese village and eventual rescue. With a pretty nurse (Ann Sears) aiding his recovery at Mount Lavinia Hospital in Ceylon, Shears is confident of a medical discharge, because “I’m a civilian at heart,” and aghast when Green asks if he would consider lending his unique knowledge to the team. Shears reveals that he’s an enlisted man who stole the rank of a corpse to ensure better treatment, but the Navy, eager to unload its hot potato, has temporarily transferred him to Force 316.

His reaction recalls that of Captain Virgil Hilts (Steve McQueen) to the similar request in The Great Escape (1963); also echoing my other favorite POW movie is the presence of Donald, who played its senior British officer. It’s easy, dazzled by Guinness and Holden, to sell short this stellar supporting cast, and Donald completed my personal trifecta as Dr. Roney in Quatermass and the Pit (1967). Morell, who coincidentally played Quatermass in the original BBC version and made an excellent Watson opposite Peter Cushing in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), was a regular in Hammer films, also appearing in Ben-Hur (1959) with Hawkins, whom I recall best as Quintus Arrius in William Wyler’s epic.

An ex-professor of Oriental languages who speaks Siamese, Warden heads up the team, whose fourth member, as in The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Where Eagles Dare (1968), dies in the parachute jump. This is one of the incidents with which the scenarists beef up and dramatize their long jungle trek, accompanied by female Siamese bearers with their own “cute” theme, but the interruption of their idyllic interlude at a waterfall has far-reaching consequences. Through Joyce’s hesitation to use his knife in cold blood—a concern from the start—Warden suffers a foot wound that slows them as they race to reach the bridge before the first train, loaded with V.I.P.s and matériel, makes it a doubly tempting target.

Refusing to leave Warden behind in the jungle, Shears delivers this impassioned speech (above): “You make me sick with your heroics! There’s a stench of death about you. You carry it in your pack like the plague. Explosives and L-pills [i.e., suicide tablets]—they go well together, don’t they? And with you it’s just one thing or the other: destroy a bridge or destroy yourself. This is just a game, this war! You and Colonel Nicholson, you’re two of a kind, crazy with courage. For what? How to die like a gentleman, how to die by the rules—when the only important thing is how to live like a human being!” For me, that sums up both the essence of his character and the power of Holden’s great performance.

During the night, while Shears and Joyce float the plastic explosives downstream by raft to place the charges on the piles, we see the celebration Boulle had only alluded to, with prisoners cavorting in drag. It allows Nicholson to state his side eloquently (“You have survived with honor. That, and more: here in the wilderness, you have turned defeat into victory”), while in another effective visualization, a sign (below) proclaims that “This bridge was designed and constructed by soldiers of the British Army.” Warden’s wound forces him to remain above as Joyce—the best swimmer among them—lies concealed on the far side of the Kwai with the plunger, and faces the unenviable task of swimming back under fire.

As in the novel, things fall apart as the river goes down in the night, exposing the wire to Nicholson, whose men have marched off to another camp while he remained to transport the sick men there with Clipton. When the two colonels descend to investigate, Joyce at last uses his knife on Saito (“Good boy!” exults Warden) yet, perhaps understandably, is unable—having identified himself as a fellow British officer—to prevent Nicholson from sounding the alarm by killing him. Swimming across, Shears succumbs to enemy bullets just after being recognized by Nicholson (“You!”), who is struck by Warden’s mortar fire and, asking “What have I done?” (below), collapses onto the plunger, destroying bridge and train.

Oh, yes, there is one other tiny change—in the book, the bridge don’t get blowed up, even if Warden’s secondary device does derail the train. It is, in fact, doubly anti-climactic, as Boulle fast-forwards from Nicholson’s “Help!” to sole survivor Warden, telling Green a month later how he’d shelled the group to ensure that Shears or Joyce could not be taken alive (“It was really the only proper action I could have taken”). I’m reminded of another Spiegel production, John Huston’s The African Queen (1951), which ends as the Königen Luise is sunk by the submerged wreck of the Queen, a similar crowd-pleaser not found in the source novel, in that case written by C.S. Forester, the creator of Horatio Hornblower.

The literal last word is left to Clipton, who surveys the carnage below and can only repeat, “Madness,” also echoing recent SILVER viewing, Wolfgang Petersen’s Das Boot (1981). In a peculiarly German gesture, the silently stricken war correspondent Werner (Herbert Grönemeyer), a stand-in for author Lothar-Günther Buchheim, falls to his knees (above) as the U-96, having survived so many travails, is sunk by an air raid on the harbor at La Rochelle, and its unnamed captain (Jürgen Prochnow) aptly dies after it slips under the water. Yet one cannot—or at least I won’t—say that Nicholson was totally in the wrong, since even Clipton was forced to acknowledge the salutary effect of building the bridge on the men…

.jpg)