There were occasions when I felt he was miscast—which is not the same thing as giving a bad performance—e.g., as Rochester in Jane Eyre (1996) or Duke Leto Atreides in the second of the seemingly endless versions of Dune (2000). But he endeared himself to me from his very first film, Ken Russell’s 1980 adaptation of Paddy Chayefsky’s Altered States, one of my quintessential “love stories that’s not obviously a love story,” like James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989). I still remember how powerful I found the Altered States trailer when I was working at Cinestudio back in my Trinity College days in Hartford.

The less said about Peter Yates’s Eyewitness (1981), the better, despite the presence of Hurt and BOF fave Sigourney Weaver; interestingly, I considered Breaking Away (1979) overrated and actively disliked Four Friends (1981), both sans Hurt but also written by Steve Tesich. I have dim yet favorable memories of the thriller Gorky Park (1983), and especially of his Oscar-winning turn opposite Raul Julia in Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985), while if I was, as Dad used to say, “just whelmed” by Children of a Lesser God (1986) and Broadcast News (1987), it wasn’t due to any deficiency in his performances, both also nominated. In fairness, the latter contains one of my favorite lines, when Albert Brooks says to Holly Hunter, “Okay, I’ll meet you at the place near the thing where we went that time,” a classic example of the “private language” between longtime friends or lovers that to this day we willfully misquote chez nous as “I’ll meet you at the place by the thing.”

Until the End of the World (1991) was a typically quirky opus from Wim Wenders, whose The American Friend (1977) and Paris, Texas (1984) are both on my (long) short list; it has the added attraction of newly composed and deliberately futuristic songs by, among others, my second-favorite band, Talking Heads (“Sax and Violins”), and my daughter’s favorite, U2 (the title tune). I’m sorry to say I have yet to see Hurt’s final Oscar-nominated performance, in David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005), which I naturally confuse with Wenders’s non-Hurt The End of Violence (1997). Of his work that I’ve seen from this millennium—ouch—Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), of which a re-viewing is overdue, stands out most in my mind.

To me, however, Hurt’s work (see selected B100 reviews) will always be defined by his collaborations with writer/director Lawrence Kasdan, and if I was less transported than some by Body Heat (1981), it’s because I was too busy being outraged over his betrayal by Kathleen Turner. (In my mind, I made a very brief sequel entitled Ned Racine’s Revenge, in which we see him emerge from the foliage on her tropical beach and blow her away. The end.) I thought The Accidental Tourist (1988) was solid, even if it did have that Turner broad—whom I’ve unsurprisingly never liked—as well, and you couldn’t ask for better compensation than Geena Davis.

I Love You to Death (1990) epitomizes my “underdog favorites,” and in this case I am joined by Madame BOF; we simply cannot understand why that delightful film is not better regarded. If I had to pick my signature Hurt role, it would be sometime talk-radio host Nick Carlton in The Big Chill (1983), which is not only one of my all-time favorites but also, in my humble opinion, one of those that best employs a soundtrack of existing songs.

Less than 48 hours after reading Hurt’s obit in Time, I was following Madame BOF to her VW dealership so that we could drop off her Jetta for some routine maintenance, and what should come on the radio but “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” which I dearly love specifically from its use in The Big Chill. Between that and the always welcome reminder of my oldest friend and best man, Rolling Stones über-fan Fred Pennington, I positively wept tears of mingled joy and sorrow.

Nick, you may always consider me part of your “small, deeply disturbed following.”

You will be missed.

Bradley out.

Posted in Uncategorized | 4 Comments »

Just when you thought—AGAIN—that this year couldn’t get any worse, John le Carré is dead of pneumonia at 89, having been a huge part of my life for 40 years.

More often than not, when I fall in love with an author’s work, our relationship begins via the screen, and le Carré (aka David John Moore Cornwell) was no exception. I was just starting my senior year in high school in 1980 when the 1979 BBC miniseries adapted by Arthur Hopcraft from Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974, hereinafter TTSS), and starring Alec Guinness as George Smiley, debuted on PBS here in the U.S. I’m sure I was at least dimly aware of le Carré and his breakthrough third novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963, hereinafter TSWCIFTC), although I can’t recall if I’d yet seen Martin Ritt’s 1965 film; doubtless Guinness’s face plastered all over the ads was all I needed to get me to tune in…and the rest was history.

Details are unsurprisingly hazy after four decades, but I do recall very specifically that the miniseries and, by extension, le Carré’s work were a big thing for my then-girlfriend (soon supplanted, officially as of our first date on Valentine’s Day 1981, by the future Madame BOF) and me. We speculated endlessly on the identity of Gerald, the mole inside British intelligence, aka The Circus; Smiley’s People (1979), the concluding volume in the Karla Trilogy after The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), had only recently been published, and as soon as we could do so safely without spoiling the end of TTSS, we devoured the books as well. That shared interest and enthusiasm is actually one of the happiest memories associated with the last of my (few) “Dreaded Ex-Girlfriends.”

From the first moment, with the Russian nesting-doll images and Geoffrey Burgon’s at once mournful and sinister score for its title sequence, you knew you were in for something special, and to this day, TTSS remains one of my favorite adaptations of anything, by anyone, anywhere, ever. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve seen it, especially after its long-overdue DVD release replaced my aging VHS recording, yet despite repeated viewings, a running time of almost five hours, and knowing the ending in advance, I never find a frame of it less than riveting. Guinness’s perfection is attested to by the fact that le Carré later said he couldn’t think of Smiley without seeing the actor in his head; most of the rest of the cast was new to me, although I was probably rare among U.S. viewers in saying, “Hey, look—it’s Ian Bannen!”

One of my many peculiarities is that as much as I may love an author’s work, I frequently pledge my allegiance to a specific character and go no further; the classic example is Agatha Christie, all of whose Hercule Poirot books I have, but nothing else except the ubiquitous Ten Little Indians (1939). So with le Carré, I have yet to read anything outside the Smiley canon, and still haven’t gotten around to the post-Karla books that include Smiley and/or are set in the same “universe,” i.e., The Russia House (1989), The Secret Pilgrim (1990), The Night Manager (1993), and A Legacy of Spies (2017); even Smiley’s literary career path is fascinating, oscillating as he did between center stage and supporting roles over the decades. Herewith a BOF-centric look at the le Carré oeuvre…

- Call for the Dead (1961): Smiley is front and center in his debut, a straight-up espionage yarn that planted many of the seeds harvested in TSWCIFTC. It was adapted by Goldfinger (1964) alumnus Paul Dehn and the great Sidney Lumet—reunited on the sublime 1974 version of Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934)—as The Deadly Affair (1967), with James Mason as “Charles Dobbs.” I wasn’t wowed by that one on my single viewing decades ago, but with that pedigree, it’s obviously ripe for reappraisal.

- A Murder of Quality (1962): Smiley still stars, but this—as its title suggests—is more of a murder mystery. It was made into a 1991 British TV-movie with Denholm Elliott, which I’m pretty sure I saw but would also like to revisit.

- TSWCIFTC: This novel’s indirect influence on my life is incalculable, for when my future friend and idol Elleston Trevor decided, like le Carré, to create a spy who was in many ways the antithesis of James Bond—as he did under his Adam Hall pseudonym in The Quiller Memorandum (1965)—he was inspired not by reading the actual book, which I believe he never did, but by a review of it. Wow. Typically, I know the film version better; also co-written by Dehn, with Guy Trosper, it epitomizes the always talented and impressively diverse directorial career of Martin Ritt. Despite its shattering ending, I consider it perhaps the definitive Cold War movie, with a superb Richard Burton heading a cast that includes Claire Bloom, Oskar Werner, Cyril Cusack, Peter van Eyck, Michael Hordern, Bernard (M) Lee, and Rupert Davies as Smiley, a supporting character.

- The Looking Glass War (1965): Smiley is once again marginalized in the novel, and dropped entirely from the 1970 screen version; this time, however, the whopping downer of an ending did put me off the story in both incarnations.

- TTSS: One of my favorite novels. Besotted as I am with the miniseries, I was convinced when I learned it would be remade as a 2011 film that, Gary Oldman or no Gary Oldman, they could never justice to it in a feature’s running time. While I naturally prefer the original, I’m delighted to admit I was wrong; it’s excellent.

- The Honourable Schoolboy: I have mixed feelings about the fact that when trying to bring the Karla Trilogy to the screen, the BBC skipped this one completely and went straight to Smiley’s People. On the one hand, that naturally offends me on general principle. On the other hand, it’s a difficult and downbeat book and, more to the point, actually can be removed from the overall storyline without leaving much of a ripple in a way that, say, The Two Towers never could. Certainly as played (admittedly well) by Joss Ackland in TTSS, protagonist Jerry Westerby would have left something to be desired as a leading man. Maybe someday.

- Smiley’s People: The follow-up miniseries is almost as good as TTSS, and that’s saying a lot; this time, le Carré himself shares screenwriting credit with another Bond veteran, John Hopkins of Thunderball (1965). With few exceptions—most regrettably the loss of Michael Jayston (coincidentally the small screen’s elusive Quiller), replaced by the otherwise inoffensive Michael Byrne as Peter Guillam—the cast returns, with such welcome new additions as genre veterans Michael Gough and Ingrid Pitt. New composer Patrick Gowers is equally up to snuff.

- The Little Drummer Girl (1983): Never read this non-Smiley novel (and, to be blunt, perhaps never will), but did see, was underwhelmed by, and have largely forgotten George Roy Hill’s depressing 1984 feature version with Diane Keaton.

- A Perfect Spy (1986): Also never read this non-Smiley semi-autobiographical novel (and, to be blunt, perhaps never will), but did see the 1987 miniseries, which introduced me—as the protagonist’s tale-spinning father—to Ray McAnally, later seen in The Mission (1986) and another of my favorite spy films, the 1987 adaptation of Frederick Forsyth’s The Fourth Protocol (1984).

- The Russia House: Saw, and have completely forgotten, Fred Schepisi’s 1990 adaptation of this as-yet-unread novel, starring the late, lamented Sean Connery.

- The Tailor of Panama (1986): This is one non-Smiley novel for which I’ll make an exception, given not only how much I loved John Boorman’s 2001 adaptation (with Pierce Brosnan, Geoffrey Rush, and Jamie Lee Curtis), but also because it’s his take on Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana (1958), filmed with Guinness in 1959 by Carol Reed and Greene, makers of the classic The Third Man (1949).

- The Constant Gardener (2001): Saw and admired the 2005 screen version with Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz, but didn’t go nuts over it the way my daughter did, and quite frankly may or may not get around to reading the novel. We’ll see.

- A Legacy of Spies: I’ll never forget where I was when I learned of the existence of this book, both a prequel and sequel to TSWCIFTC, which finally puts Smiley back in the spotlight. I was with my mother and Madame BOF at “The Shack,” the Bradley family’s humble vacation home in God’s Country North (i.e., Vermont), and chanced to look at Mom’s copy of The New York Times Book Review, which I normally never see. There I saw a huge ad touting Smiley’s return, and let out a whoop that was probably heard all the way down in God’s Country proper (i.e., Connecticut). Of course, grindingly methodical as I am, I still have to find time to get through the three intervening books before I get to this, but hopefully I still have a few years left in me.

Posted in Uncategorized | 4 Comments »

…or would be if any theaters were open:

David Cronenberg’s terrifying new film,

COVID-EODROME

Sleazy lowlife Max Renn (Bradley Cooper) runs an Internet streaming site, and when looking for new material to show, he discovers a snuff broadcast called COVID-eodrome. But it is more than an Internet show—it’s a terrifying experiment that breaks the fourth wall into “unreality TV,” spreading a deadly pandemic among unwitting viewers. Max’s sado-masochistic girlfriend, Nicki Brand (Lady Gaga), decides to travel to Pittsburgh, where the show is based, to audition. Max investigates further, and through a video by the Internet prophet Conner O’Virus (Conan O’Brien in a cleverly macabre piece of stunt casting), he learns of a global conspiracy that gives the phrase “computer virus” a whole new meaning. Before you can say, “Who was that unmasked man?,” Max is caught in the middle of the forces that created COVID-eodrome and the forces that want to control it, his body itself turning into the ultimate Petri dish. Never has Cronenberg’s unique form of “body horror” been used to timelier effect than in this gruesome thriller ripped from the international headlines.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

My dear friend, we were so blessed to have you, even for so absurdly short a time. Now you’re in Heaven, where it’s Movie Night every night. In heartbroken tribute, through a blur of tears, I offer these lyrics, (re)written years ago, which are how I will always remember you. I love you, man.

Addendum: At least you lived long enough to see your beloved (yes I use that word with tearful irony) Chiefs win the Super Bowl. At the time I probably said something about how you could then die happy. Now I wish my tongue had been torn out by the roots rather than suggest such a thing even in jest.

“The Host with the Most”

(Lennon/McCartney/Bradley)

Night after night, alone in his flat

The man with the wall of hats is talking just to his cat

But once in a while they join him

For the fun and the films and food

And he never lets them help him

But the host with the most

Sees his friends coming ‘round

And the candles are lit

When the sun’s going down

Kaiju and gore, presented with pride

The man of a thousand movies keeps him amply supplied

But don’t ask about Blake Edwards

Or the films he appears to hate

And he never seems to show them

But the host with the most

Sees his friends coming ‘round

And the candles are lit

When the sun’s going down

And he always serves your favorites

He just does what he wants to do

And he doesn’t charge admission

But the host with the most

Sees his friends coming ‘round

And the candles are lit

When the sun’s going down

He doesn’t go for breakfast

Or send you on your way

He just sleeps in

The host with the most

Sees his friends coming ‘round

And the candles are lit

When the sun’s going down

Tom…

Posted in Uncategorized | 7 Comments »

I’m delighted to report that my good friends and colleagues at the bare•bones e-zine (also behind Marvel University and other blogs I have contributed to in varying degrees) are returning to print with a third incarnation of their eponymous digest, which began life as The Scream Factory. My MU faculty brethren—and fellow Penguin USA (PUSA) alumni—Professors Thomas Flynn and Gilbert Colon are represented alongside me in the first issue, now shipping. Imagine my surprise when Dean Peter Enfantino and retired Professor John Scoleri broke the news, and I learned for the first time that my article, an exhaustive comparison between Ray Bradbury’s seminal classic The Martian Chronicles and its screen adaptations, had been featured on the nifty cover as well!

Not coincidentally, the piece is a perfect snapshot of what I’m doing with my new book, whose title du jour is The Group: Sixty Years of California Sorcery on Screen. I had, of course, done a detailed analysis of the 1980 Chronicles miniseries for Richard Matheson on Screen, which I’ve distilled for the Group history. Yet because the latter encompasses not only Richard and Ray but also such fellow “Sorcerers” as Robert Bloch, George Clayton Johnson, William F. Nolan, Jerry Sohl (each of whom I interviewed extensively), and Charles Beaumont, all the other Chronicles adaptations, most notably those done for The Ray Bradbury Theater, have become fair play, and synthesizing all of the relevant coverage from both books made for a nicely self-contained piece.

Which brings me to my second piece of news, i.e., that the irrepressible British journalist Gem Wheeler has once again interviewed and quoted me at great length for a Group-related article in SciFiNow. Some of you may recall her citing me as a Matheson expert for prior pieces about the Night Stalker franchise and Richard’s overall career; in #167, she weighs in with an overview of Edgar Allan Poe’s work, devoting an entire sidebar (which, I note immodestly, is basically one long quote by me) to director Roger Corman’s eight-film “Poe Cycle.” She, too, benefits from my being on the cusp of the books, since I’ve now covered the three entries to which Beaumont and/or fellow Group member Ray Russell contributed, as well as the four written by Matheson.

Last but far from least, I’d like to offer a big “blast from the past” shout-out to a fellow Viking Penguin publicity vet, Roel Torres, who joined us in the mid-90s during The Great PUSA to Columbia House Migration™ that eventually included Tom, Gilbert, and Professor Joe Tura, leaving Professor Chris Blake and me the last men standing of the Movie Night Musketeers. As Chris put it, “Since we were in the same department, and both comics fans, and since Roel is an insanely clever guy, we got to be friends,” making pilgrimages to our cinematic second home of Film Forum. Roel recently resurfaced via a comment on one of my posts to report that—a brave soul—he will be reading through my backlog, so please reward him by checking out his comics!

Bradley out…and about.

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

What I’ve Been Watching: The Holcroft Covenant (1985).

Who’s Responsible: John Frankenheimer (director); George Axelrod, Edward Anhalt, John Hopkins (screenwriters); Michael Caine, Anthony Andrews, Victoria Tennant (stars).

Why I Watched It: Several reasons, most notably Frankenheimer.

Seen It Before? Apparently so.

Likelihood of Seeing It Again (1-10): 9.

Likelihood the Guys Will Rib Me for Watching It (1-10): 2.

Totally Subjective BOF Rating (1-10): 4.

And? If you were The GREAT John Frankenheimer (TGJF), having directed some of the cinema’s best thrillers—e.g., The Manchurian Candidate, Seven Days in May, Black Sunday—and were adapting one of the mega-bestsellers by Robert Ludlum—e.g., The Osterman Weekend, The Bourne Identity—whom would you get to write the screenplay?

- A: George Axelrod, your Manchurian colleague, an Oscar nominee for—of all things—Breakfast at Tiffany’s?

- B: Edward Anhalt, who worked with John Sturges on the Cold War thriller The Satan Bug, based on a pseudonymous Alistair MacLean novel, as well as the underrated O.K. Corral sequel Hour of the Gun?

- C: John Hopkins, whose espionage credentials range from adaptations of Ian Fleming (Thunderball) to John le Carré (Smiley’s People)?

The answer is “D: All of the above,” yet alas, regardless of their, um, caliber, the old adage about the inverse relationship between a script’s coherency and the number of scenarists remains true here. (Technically, per Wikipedia, Hopkins was rewritten by Anhalt, and then in turn by Axelrod—injecting humor—when TGJF came on board.)

Architect Noel Holcroft (Caine, replacing James Caan, who mercifully walked just prior to shooting) was spirited out of Nazi Germany as a baby by mom Althene (Lilli Palmer, long admired by TGJF)—now a NYC bookseller—to escape biological father Heinrich Clausen. Summoned to Geneva by banker Ernst Manfredi (Michael Lonsdale, later of TGJF’s Ronin), he gets astounding news: a troika of generals who turned against Hitler siphoned off a fortune, now earmarked as recompense for the crimes of the Third Reich. The titular document, giving Noel control of $4.5 billion to be used for good, will only be activated when signed by the sons of that suicidal triumvirate, who must now be located.

You buying it? Nope, nor is Althene, who regards her ex’s last-minute conversion as a bunch of hooey. Arrayed on her side are a secretive, wheelchair-bound Oberst (Richard Munch, whom I finally recognized as the bespectacled war-games planner in The Longest Day) and a pixieish MI5 agent, Commander Leighton (Bernard Hepton, indelible as Toby Esterhase in the original Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People). But Noel really wants to believe, so the hunt is on for Erich Kessler (Mario Adorf from the 1965 version of Ten Little Indians), hiding in plain sight as a famous orchestra conductor Jürgen Mass, and journalist Jonathan Tennyson (Andrews, in a slimy mustache that cannot be trusted).

Tennyson (né von Tiebolt) has spent his life on the run with sister Helden (Tennant, in a role conflating two Ludlum characters), who soon bonds—and beds—with Noel on his whirlwind European tour. We’ve seen Tennant do the sultry sidewinder routine before, betraying Steve Martin in All of Me, so it comes as no surprise here, with the added kink of incestuous-sibling sex. Turns out the whole thing was a scheme to facilitate the Fourth Reich by, if I’m understanding this convoluted plot correctly, using the dough to fund and consolidate the world’s greatest terrorists, sowing sufficient anarchy to create a need for a strong controlling hand, which Führer von Tiebolt et al. will be only too glad to provide.

To be blunt, my gut reaction was that I didn’t like the way this movie looks, sounds, or feels. I was ready to attribute the first to the cheesy, sleazy touch of Cannon Films, for whom TGJF next made the Elmore Leonard adaptation 52 Pick-Up, until I realized they were just the home-video distributors. In our interview, he said the producers “couldn’t afford to have [the film] come out and do well because there was so much crap that went on with EMI and all that that you just don’t know….[U.S. distributor] Universal saw the picture. They loved [it and] said, ‘We want to really give this a hell of a ride, but what we need as a backup, just in case it doesn’t work, we need to have the ancillary rights.’

“In other words, we need to have the cable and cassette rights to back up the expenditure we’re going to do on prints and ads, and EMI said, ‘No, you can’t have those.’ Now, don’t ask me why they said that, because I don’t want to get sued, but the point is that Universal said, ‘Well, then, how can you ask us to spend all this money to publicize this picture if we don’t have any backup to protect our investment on the down side?’ So Universal then just fulfilled its contractual obligation and opened it in, like, a hundred theaters and then put it onto video. It was just so disappointing, because I thought the picture was pretty good, and Ludlum loved it,” so maybe it’s just that ugly ’80s patina.

The film benefits from many Berlin and London locations, while cinematographer Gerry Fisher, a frequent collaborator of Joseph Losey’s making his first of three for TGJF, was no stumblebum. John agreed that it “had a lot of stylistic similarities to The Manchurian Candidate,” including frequently tilted camera angles, if perhaps not used as successfully here. As for the soundtrack, mono-monikered composer Stanislas provided just the type of tinny synth score that also helped to give ’80s movies a bad name, but my reservations regarding the overall feel are tougher to quantify; much of it has to do with the efforts by John and Axelrod to add humor, which in my opinion give it an uneven or uncertain tone.

Outright comedy is unequivocally not Frankenheimer’s forte (see—or better yet don’t—his bombs The Extraordinary Seaman or 99 and 44/100% Dead), but while leavening an espionage thriller with humor is a time-honored m.o., notably in the Harry Palmer series Caine kicked off with The Ipcress File, they just don’t seem to mesh here. I share John’s admiration for Caine, one of my favorite actors, yet everything seems slightly off and I’m not sure whom to blame. Adding to the bizarrerie, Helden tries to stay under the radar by concealing Noel amid the depraved demimonde of Berlin, including a Weimarian carnival concocted by Frankenheimer, which also allows for some presumably commercial nudity.

Posted in Uncategorized | 3 Comments »

Concluding our look at Roger Corman’s cannibalization of Soviet SF films.

Ruble-pinching Roger got his best ROI with Pavel Klushantsev’s Planeta Bur (Planet of Storms, 1962), which he cannibalized not once, but twice. Harrington’s makeover is far less comprehensive, adding expository scenes of Rathbone and Faith Domergue of This Island Earth (1955) fame, so Voyage to a/the [onscreen titles differ] Prehistoric Planet (1965)—sold directly to TV via AIP—is credited to “John Sebastian.” Billed as “Derek Thomas,” Peter Bogdanovich, uh, fleshed out Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women (1966) with Mamie Van Doren leading the titular telepathic, amphibious Venusians; it is not be confused with Arthur C. Pierce’s forlorn Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966).

I’ll occasionally see an example of what I call “scholarship” (one of my highest words of praise) that begs commendation, and Retromedia’s four-film The Roger Corman Russian Sci-Fi Collection—which Professor Tom, The Host with the Most™, whipped out for our most recent Movie Night faculty gathering in Queens—is one of them. The absence of Queen of Blood is compensated for with a subtitled print of Planeta Bur, enabling one to compare the original with both adulterated versions. A featurette, Being Mamie, offers a career-spanning interview with Van Doren, and if you look REALLY closely, you can spot Richard Matheson’s name at the bottom of the poster for The Beat Generation (1959).

Adapted by Klushantsev and Aleksandr Kazantsev from the latter’s novel, Planeta Bur opens with three Soviet “cosmic expedition starships” approaching Venus after a trip of some 140 million miles, only to have a meteorite destroy the Cappella, forcing a change in plans. To ensure sufficient fuel for the return trip, one ship must remain in orbit, so—leaving love interest Masha Ivanova (Kyunna Ignatova) aloft to process data and transmit it to Earth—Ivan Scherba (Yuri Sarantsev) descends in the Vega’s glider with Allan Kern (Georgi Tejkh) and his humanoid robot, John. Their mission is to find a suitable landing spot for the Sirius, returning therein, but they are forced down in a swamp after doing so.

Ilya Vassilievich Vershinin (Vladimir Yemelyanov), Alexey Alyosha (Gennadi Vernov), and Roman Bobrov (Georgi Zhzhyonov) set off from the Sirius in their ATV (above) to aid them, after Alexey is saved from a tentacled plant. Meanwhile (interestingly, in the transitions, scenes fade to red rather than black!), Ivan fends off lizard-men as Kern assembles John, and they make their way on foot, briefly sidelined by fever while taking refuge in a cave from a storm. Beset by pterodactyl-like creatures, the Sirius team submerges their ATV and finds a dragon statue with a ruby eye underwater, fueling discussions about possible inhabitants—indigenous or transplanted—and the melodious voices heard since arriving.

A red spot seen from orbit is revealed as a volcano, and John (above) tries to carry the men across the lava, although Isaac Asimov would cringe at the scene where they disconnect his self-protection program to stop him from lightening his load when his feet begin to melt. The ATV arrives just in time, and—like Soviet dwarves—the reunited men sing a happy song as they return to the Sirius, quickly changing their tune as a quake threatens to undermine it. Setting up a meteorological station while preparing to blast off, Alexey makes a crude tool out of a curious rock he had found, which breaks open to reveal a sculpted humanoid face; after they depart, we indistinctly see a robed figure reflected in the water of a pool…

“Sebastian” Americanized the names of the astronauts, but left those of the ships and the basic narrative intact as Professor Hartman (Rathbone) calls the shots from Lunar Station 7 (in lieu of Klushantsev’s offscreen and Earthbound mission control). Scenes of Masha were replaced by newly shot footage of Domergue (above), sporting a beehive hairdo and reeking of apathy, as Marsha Evans. Harrington said, “all I did was just shoot a couple of scenes of somebody in a space station [below]. The totality of [Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet] is the Soviet film dubbed, so that’s why it has another name on it. I really just did a couple of those scenes as a courtesy, but I don’t consider that I have anything to do with the film.”

Rathbone shot his scenes for both films back-to-back, utilizing the same set and costume. He “was very vital. He knew all of his lines; he was not in any way enfeebled. He was a man of great personal charm, and I really enjoyed talking to him between takes. It was a great privilege to work with him….[but Queen] was such a low-budget film, and we shot the whole thing in seven days. That meant that we were shooting non-union again, and I was shooting from early morning until very late at night….[which] was a strain on him, and he wasn’t paid sufficient overtime, so he was very upset about that. I had nothing to do with that, of course; I was just determined to shoot the film to the best of my ability…”

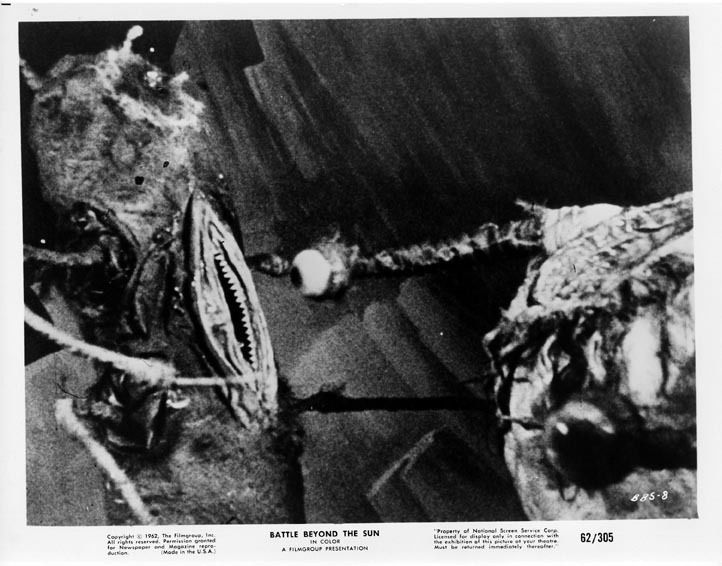

Prehistoric Women gets the deluxe widescreen treatment; Retromedia founder/Corman cohort Fred Olen Ray joins David DeCoteau for a commentary, and even reproduces the French photo novel La Planète des Tempêtes. Pilfering the space-exploration prologue from Battle Beyond the Sun, “Thomas” maintains Harrington’s dubbing and names, but repurposes the Planeta Bur footage sans female astronaut, so “Marsha” is the “code name for Earth control.” Bogdanovich narrates the film, presented as a flashback by Andre (né Alexey), while the three starships now represent separate missions, with the third sent to rescue the second, refueling at U.S. space station Texas via more chunks of Nebo Zovyot.

It is not until 33 minutes in that we first glimpse Moana (Van Doren) and her “sisters,” including Margot Hartman—who appeared in her husband Del Tenney’s Stamford-shot Curse of the Living Corpse (1964)—as Mayaway. They are first seen draped on a rocky shore like so much jetsam (above), clad in frilly white bell-bottoms and scallop-shell brassieres; with voiceovers instead of spoken dialogue, the actresses need do little but stare into the camera with expressions ranging from intent to vacant. Seeking to avenge the death of their pterodactyl-like “god,” killed by the humans, they incite the volcanic eruption and the destabilization that threatens the takeoff, then erect a lava-covered John in his place (below).

Ray’s commentary with fellow director DeCoteau is replete with entertaining anecdotes about Corman and the wild world of low-budget filmmaking, although concerning these cinematic examples of détente, it told me little I did not know. Women occupies a modest percentage of Being Mamie, created in 2003 for a stand-alone DVD, but it’s a fun way to, um, round out the set. The “Platinum Powerhouse” holds forth irreverently on everything from endless comparisons with Monroe and Mansfield—both of whom she has outlived for more than half a century—to her work with exploitation legend Albert Zugsmith (e.g., that Matheson misfire) and in the schlock classic The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966; below).

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

Putting the “International” into American International Pictures, Roger Corman acquired U.S. distribution rights to several Soviet SF films, ransacked them for their impressive (or at least economically obtained) special-effects footage, and deputized three of his famous protégés to morph them into four “new” movies. The level of insult to the original varied considerably: Francis Ford Coppola’s Battle Beyond the Sun (1962) mostly just hacked up and redubbed Nebo Zovyot (The Heavens Call; 1959), directed by Mikhail Karzhukov and Aleksandr Kozyr. Using the nom de cinéma of “Thomas Colchart,” he deleted all the boring Commie agitprop and inserted—as it were—monsters suggesting human genitalia.

In 1997, Earth is divided into North Hemis and South Hemis (clearly analogs for the U.S. and U.S.S.R., respectively); learning that the latter plans to send the Mercury to Mars, or perhaps the other way around, the former gets the jump on them in the Typhoon, yet it comes to grief and is abandoned after its crew is rescued. The Mercury now lacks enough fuel to return home, forcing them to land on the asteroid Angkor, where they set up an antenna and we dimly see the battling Genitaliasauruses. An unmanned fuel ship crashes, but South Hemis sends a second ship, whose pilot heroically dies completing his mission, and both crews make it safely back to Mother Earth to set up peaceful coexistence, ending the bitter, years-long rivalry. If only.

Conversely, writer-director Curtis Harrington (1926-2007) added so much—even dollops of Nebo Zovyot—to Mechte Navstrechu (A Dream Come True; 1963), which Karzhukov directed with Otar Koberidze, that Queen of Blood (aka Planet of Blood; 1966) is a “real” movie in its own right, aptly bearing his own name. It stars Florence Marl[e]y in the title role, with genre legend Basil Rathbone, a young Dennis Hopper (with Marly below), and John Saxon. Asked in our Filmfax interview (c. 2004) about being reunited with Judi Meredith, his co-star in Charles F. Haas’s Summer Love (1957), Saxon said, “we were friendly, and it was fun to see her again. Her career was kind of waning….[That] lasted about seven shooting days.

“Most of the footage…had all the special effects of people in these costumes, and you couldn’t see their faces. So we just dubbed in the story with Americans, and maybe 25% or 30% of it was already there, in special effects that came from the footage that they had bought from this other film. All I can remember was that Dennis Hopper couldn’t keep a straight face in any of the scenes, and it was one of Basil Rathbone’s last appearances [he died the following year]. He came off a spaceship in one scene and that was it. He was old and tired and, I think, ill. Florence Marly was intense and striking. Curtis Harrington admired her a lot. He [recently said] how well [it] holds up. I haven’t seen it for years.”

By 1990, the Moon has been colonized and expeditions planned to Mars and Venus; Dr. Farraday (Rathbone) reports that deciphered alien signals say an ambassador is en route, while a probe arrives with a video log of aliens crash-landing on Mars and sending out an S.O.S. A mission planned for six months hence is thus accelerated, with Allan Brennen (Saxon, above), Laura James (Meredith), and Paul Grant (Hopper) aboard the Oceano, which is damaged by a sunburst. When one dead astronaut is located in the alien wreck, Farraday posits that the rest escaped aboard a rescue craft, spotted on the Martian moon of Phobos as Allan and Tony Barrata (Don Eitner) are placing satellites in orbit aboard the Meteor.

They find an alien queen—billed simply as “?”—alive, but with room on the Meteor only for two, Allan leaves Tony there to await the Oceano II. The alien refuses solid food and freaks out at the sight of a hypodermic; when he sees her bloody lips after Paul is drained, Allan advocates destruction, and while Anders Brockman (Robert Boon) argues in favor of feeding her, he’s next on the menu when the plasma runs out. The alien burns through her restraints with heat vision and is feeding on Allen when Laura sees and scratches her, but the hemophiliac queen, who bleeds to death, has left a clutch of jelly-like eggs, which Farraday’s aide (a gleeful Forrest J. Ackerman, above) preserves once they’ve returned to Earth.

I also interviewed Harrington, who had given Hopper his first lead in Night Tide (1961), and cast Czech blacklistee Marly, briefly seen in the Twilight Zone episode “Dead Man’s Shoes” (1/19/62). “I enjoyed doing that very much. I devised the story and worked out using the Soviet technical footage, and I was very happy to give the key role of the alien creature to Florence…whom I had admired in her European films,” he related. “That was a completely salutary experience, even though it was a very low budget, done in a short time, but it is the film that got me my contract at Universal Studios,” where he and Queen of Blood producer George Edwards resumed their long collaboration with Games (1967).

Trying to match the Soviet footage “was a technical challenge, but I think I did it very well. We worked it all out very carefully. We had a special effects company that made the space suits to look exactly like the Russian ones, and it mainly was a problem at the first in the lab, matching up the footage of the two when I would cut into close-ups of our people and so on. But we accomplished it.” Regarding the appearance by Ackerman, he said the literary agent and editor of Famous Monsters of Filmland (see my seminal first issue below) “had been a personal friend of mine since [the] early days…[I had first met future collaborator Kenneth Anger] when we were both quite young at a film society in Hollywood that showed old films…”

Forry “used to come to the same film society…and I met him, and I had always had a great interest in the fantasy pulp magazines like Weird Tales and Unknown, so I found I had a great rapport with Forrest Ackerman. Famous Monsters was well established by then, so with all of his fans in the world, and they were the kind of people—all science fiction fans—who would be seeing the film, ‘Mr. Science Fiction’ himself, it seemed a logical thing to do. I can’t remember whether he suggested it or I suggested it, but I said, ‘Let’s do a cameo of you at the end of the film carrying the living eggs of the creature.’… Of course [he was having fun in his role]. He’s a dear man and I’m very fond of him.”

Of the similarities between Alien (1979), his film, and Edward L. Cahn’s It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958; above), he said, “I made a habit very early on never to see any film directed by Edward Cahn, a director of no talent whatsoever. It’s like Herbert Strock; I won’t go and see a film by him, either. People of absolutely no talent, and I just hated their films. So I’ve never seen that….I’m sure it’s abysmal, whatever it is. [Yes], it’s the same story. Whether the author of Alien saw my film, I have no idea, and I don’t know if it touched something off in him. I think there is a strong similarity. I wouldn’t accuse him of plagiarism per se, because I don’t even know if he saw [Queen], but I bet he did.”

To be continued.

Posted in Uncategorized | 3 Comments »

I recently made a priceless acquisition. A rare Matheson first edition? No, much more valuable: the friendship of a fellow wordsmith who—in classic girl-next-door fashion—was right under my nose, working part-time in another capacity at MBI. I refer to multi-talented author and editor Terence Hawkins, about whose impressive formal credentials (e.g., as the founding director of the Yale Writers’ Conference) you can read more on his site. After his boss kindly clued me in to the fact that Terry was “some kind of a writer,” or words to that effect, I chatted him up, quickly discovering that we share not only many literary and cinematic interests but also a certain, shall I say…unconventional sensibility.

“Some kind of a writer,” indeed: he honored me with a copy of his socko second novel, American Neolithic (to which a sequel is happily in the works), and I can only urge you to get your own. A hell of a writer but, more to the point here, a hell of a guy; our chats go straight to the heart of the Nexus, often touching on my fixations on adaptations and authors who double as screenwriters, and it’s lucky for MBI that once we get going, he’s more disciplined than I about cutting us off. On one of his visits to my office, he brought up yet another of the many hats he wears, i.e., as the prose editor of The Blue Mountain Review, an online “journal of culture” produced by the Southern Collective Experience.

Explaining that even a literal Connecticut Yankee like me is eligible because, as they put it, “Everyone is South of Somewhere,” he wondered if I might like to contribute a piece, possibly involving one of said fixations? Now, there is no sound effect or musical theme for the bizarre coincidences that proliferate in my life, yet if there were, you could cue it now, for that very morning I had started reading Clive Barker’s novella “The Hellbound Heart,” pursuant to my SILVER viewing of Hellraiser, adapted by…its author. Absent a connection to the Group, I hadn’t planned on writing anything about it, but figured that as the laserdisc is packed with extras, I might as well compare them for my own elucidation.

Well, you can do the math. After brief internal debate, I wrote the first few paragraphs of the would-be piece and sent them in a query to Terry, who replied, in effect, “Release the hounds.” And when a draft was done and submitted, I had the pleasure of actual editorial give and take (which, sadly, has not been true of all of my editors). I hope it goes without saying that his input made it a better piece. And so now, here I am on pages 63-66 of Issue#14, my byline prominently featured on the cover, yet—curiously listed under “Fiction,” but since it’s a nonfiction piece about fiction there’s a certain logic to it, and I’m not gonna look a gift horse in the mouth in any case. Thank you, my friend.

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

Before heading into New York (aka Gilbert’s City) to fulfill a years-long promise to myself—attending a rare theatrical screening of my favorite movie, Where Eagles Dare, at our beloved Film Forum—I wanted to make a little “public service announcement.” It’s to apologize for and explain the lack of new content since Christmas, although I always hope that the blog will be a valuable source of nexus-related lore for those who care to plumb its depths. Unsurprisingly, I am trying to focus my efforts on the Group history alluded to in my post on John Brosnan, rather than on BOF, since my day job at MBI and family/home commitments so sharply curtail what I laughingly call my “free time,” although I do hope to announce a surprise side project here soon.

Meanwhile, The Great Work™ continues, fitfully if not apace. Per my m.o. of grouping, ha ha, related sections, I’ve just finished an exhaustive analysis of the three Group-written features based on H.P. Lovecraft’s work, with typical tangents on other HPL subject matter for context. In conjunction with the project, Madame BOF and I are working our way through every episode of the original Twilight Zone—now in its fourth incarnation, I see with a sigh—and should be kicking off Season 3 once she returns from visiting our daughter in D.C. Which sub-assemblies (or tiles in the mosaic, as I conceptualize them) will form my next major initiative? That might be determined tomorrow, when I hope to be barricaded at Schloss Bradley in monastic solitude…

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »