Concluding our overview of the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers canon.

Title: Shall We Dance (1937).

Based on Stageplay? Nope; screenplay by Allan Scott and Ernest Pagano, adapted by P.J. Wolfson from a story by Lee Loeb and Harold Buchman.

Mistaken Identity? Oy. First, Fred takes a page from Ginger’s Roberta playbook as Philly hoofer Pete Peters, who styles himself as The Great Petrov, leader of a Paris ballet company. He falls in love with—stop me if you’ve heard this one—a flip book (yes, you read that right) of musical comedy star Linda Keene (Ginger), wangling his way onto the same transatlantic passage aboard the S.S. Queen Anne, where she quickly sees through his faux-Russian persona. He seems to be winning her over, using the old dog-walking ploy, when she is falsely rumored to be not only his clandestine wife but also—because she is seen knitting a replacement for her dog’s sweater (seriously; see below)—carrying his child.

Edward Everett Horton? Yes, in his series swan song as Jeffrey Baird (below), the owner of the ballet company and, as usual, the source of the problem. In an effort to dissuade Lady Denise Tarrington (Ketti Gallian), a dreaded ex-member of the company, from chasing after Petrov, he concocts a story about a secret marriage, and when she spreads it all over, everybody draws the wrong conclusions. Far from squelching the rumor once the error comes to light, Jeffrey compounds it, to Petrov’s chagrin, and Linda’s understandable ire becomes the standard romantic complication. In desperation, she even agrees to marry rich dullard Jim Montgomery (William Brisbane). Does that sound vaguely familiar…?

Eric/k(s): Blore, also making his series swan song, as Cecil Flintridge, the hotel floor manager who is continuously flummoxed by the are-they-or-aren’t-they-married routine, which dictates the access (or not) via the connecting door between their adjoining suites.

Other Colorful Characters: For me, certain actors will always be defined by a single role, and in the case of Jerome Cowan, that role is Miles Archer. For those of you in need of remedial viewing, he’s the guy of whom Sam Spade said in The Maltese Falcon (1941, above), “When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.” Here, his character—amusingly named Arthur Miller—is Linda’s own meddling manager.

Usual Suspects: Director Mark Sandrich is back after the one-off by George Stevens, who apparently put in a lot of overtime with Ginger if ya know what I mean, but seems unable to alter the downward trajectory. Even more than in Swing Time, a handful of the musical numbers are increasingly rare bright spots amid an unusually exasperating plot, and F&G don’t even dance together all that much; fittingly, this was the most expensive but least profitable entry to date. Returning screenwriter Scott is now credited alongside series newcomer Pagano, who later contributed to the Astaire/Stevens A Damsel in Distress and Rogers/Stevens Vivacious Lady (1938, above), as well as You Were Never Lovelier and Astaire’s other, lesser pairing with Rita Hayworth, You’ll Never Get Rich (1941).

Immortal Number(s): Composer George and lyricist Ira Gershwin join Jerome Kern and Irving Berlin—who became their neighbors and poker buddies when they moved to Hollywood—in the pantheon of those contributing songs to the F&G canon. (RKO even repeats the Top Hat gimmick of briefly quoting “Rhapsody in Blue” when the Gershwin name appears in the opening credits.) The tear-eliciting “They Can’t Take That Away from Me” was already my favorite of the songs written for the movie before I learned a poignant fact from the making-of documentary on this disc. George died of a brain tumor at 38 before learning that it had earned the film’s sole Academy Award nomination, and the song itself helped the grief-stricken Ira, who felt like his beloved brother and partner was talking to him. The humorous standby “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off,” source of the venerable “you like potayto and I like potahto” lyric, is a close second in my opinion.

Bonkers Number(s): Borderline. Stumbling into a jam session by the ship’s engine crew, Petrov joins them in a rendition of “Slap That Bass,” segueing into a tap number in which he is inspired by, and accompanied by massive shadows of, the engine machinery. Runner-up: F&G do their duet to “LCTWTO” on roller skates (below), displaying a virtuosity equal to that of Charlie Chaplin in The Rink (1916), which perchance I recently enjoyed.

New Dance Craze Allegedly Sweeping the Nation: Broadly speaking, representing as it does the popularization of classical dance pioneered in Rodgers and Hart’s Broadway hit On Your Toes (1936), a ballet/jazz fusion that was originally conceived as a screen vehicle for—and rejected by—Astaire, who clearly rethought his position in the interim.

White Tie and Tails? Yes, when Miller maneuvers Petrov and Linda into a duet on “They All Laughed” (at a party he throws, ostensibly to celebrate her engagement—what chutzpah!) as a way to cement their presumed, and potentially lucrative, “partnership.” And again at the end of the finale, a grotesque hybrid that combines a performance by ballerina/contortionist Harriet Hoctor, a chorus all wearing Ginger Rogers masks (don’t ask; see below), a perfunctory pas de deux following the so-so title song, and an idiotic resolution.

Unique Aspect(s): Only entry for Edmund H. North, whose credits range from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) to Patton (1970), for which he shared an Oscar with Francis Ford Coppola; per the IMDb, an uncredited “contributor to screenplay construction.”

Title: Carefree (1938).

Based on Stageplay? Nope; another Pagano/Scott screenplay, from a story and adaptation by Dudley Nichols and Hagar Wilde, based on an original idea by Marian Ainslee and Guy Endore (whew!).

Mistaken Identity? I wish. Radio star Amanda Cooper (Ginger) is dragging her feet en route to the altar, so rich fiancé Stephen Arden (Ralph Bellamy) asks his psychoanalyst pal Tony Flagg (Fred) to straighten her out. He’s immediately smitten, albeit declining to admit it to himself, and after a mercifully brief kerfuffle, in which she accidentally hears a recording of his negative preconceived notions, it becomes clear that the problem is not marriage per se, but that she’s marrying the wrong guy. As tempted as I am to call this one of the all-time great dancing-psychoanalyst films, that makes it sound more fun than it is. The desire to do something different is understandable, yet this clunker—predating Hitchcock’s stab at psychoanalysis, Spellbound, by 7 years—ain’t it, proving the adage that the quality of a script is often inversely proportional to the number of writers. When Amanda is given an anesthetic to release her inhibitions, and then accidentally taken from Tony’s office to the studio for a broadcast, her infantile behavior (breaking plate glass, kicking a cop in the pants) is clearly supposed to be hilarious, but I just found it painful. Compounding the error, Tony later tries to “fix” her love for him, which he mistakes for transference, by hypnotizing her and planting suggestions that, for example, he should be “shot down like a dog,” whereupon she gets loose again and is pursued to…you guessed it, a skeet-shooting contest at the Midwick Country Club, one of the primary settings.

Edward Everett Horton? Never again, I fear, so for simplicity’s sake, I’m deleting him from the remaining entries.

Eric/k(s): Ditto.

Other Colorful Characters: Bellamy is hardly colorful, although his diverse career encompassed silly-sod roles like this one, the nominal hero in Universal’s The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), his embodiment of FDR in Sunrise at Campobello (1960), the sinister Dr. Sapirstein in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and a latter-day resurgence opposite Don Ameche as the Duke Brothers in Trading Places (1983). Jack Carson is another matter. While watching him in Arsenic and Old Lace (1944), recent SILVER viewing, I marveled that his turn there as beat cop and aspiring playwright O’Hara and indelible role of sleazy opportunist Wally Fay in another BOF fave, Mildred Pierce (1945), showed all the range an actor could want. As Tony’s wisecracking orderly, Connors, he has little to do but catch the eye of Luella Gear as Amanda’s Aunt Cora, who at 14 years Ginger’s senior is less funny, but more age-appropriate for that, than Helen Broderick. Franklin Pangborn, a legendary comic foil for W.C. Fields and others, was the hotel manager in Flying Down to Rio, and here plays a Midwick cuckoo, club functionary Roland Hunter.

(L-R: Carson, Bellamy, Astaire)

Usual Suspects: Neither Sandrich (in his series swan song) nor the returning Irving Berlin can salvage this money-loser, the shortest and easily the worst in the F&G canon.

Immortal Number(s): By default—the Oscar-nominated “Change Partners [and Dance with Me]” is the only good song, and prophetically titled, since F&G would do just that for a decade after one more RKO film. As with “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” I prefer it as an instrumental; because Fred literally has Ginger in a trance, his Svengali-style moves as he “directs” her dance (below) are not only a cool effect but also thematically consistent.

Bonkers Number(s): Take your pick. Demonstrating coordination skills to the still-hostile Amanda, Tony hits golf balls while tap-dancing to “Since They Turned ‘Loch Lomond’ into Swing” (my, that really rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?); the best part of that one was watching my cat go after Fred’s feet and club. Later, he induces a dream to give him something to analyze, so she naturally dreams about dancing with, and falling for, him in “I Used to Be Color Blind.” You’d think the gimmick here would be that, like the song’s conceit, the film suddenly bursts into color, and apparently that was the idea, scuttled by poor-quality Technicolor tests. Instead, much of the dance (below) is in slow-motion, which seems unsuited to effects-averse Fred and, perhaps rebutting the famous “feathers” incident, obscures Ginger’s face at length with a kind of streamer attached to her wrist.

New Dance Craze Allegedly Sweeping the Nation: A generation before Elvis enjoined kids to “Do the Clam” (co-written, amusingly, by Ed Wood’s ex-squeeze, Dolores Fuller) in Girl Happy (1965), F&G urged us to do “The Yam.” At least Ginger did, although Fred refused to sing it, because he thought it was silly—imagine that!—and restricted himself to the production number (below). Purveyors of ham, jam, lamb, and Spam, take note.

White Tie and Tails? Finally, at the club (natch), for “CPADWM.”

Unique Aspect(s): Only series credit for Nichols, who won an Oscar for longtime collaborator John Ford’s The Informer (1935), or Endore, who worked with Tod Browning on Mark of the Vampire (1935) and The Devil-Doll (1936), and whose novel The Werewolf of Paris (below) was the basis for Hammer’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961).

Title: The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939).

Based on Stageplay? Nope; screenplay by Richard Sherman (not to be confused with Richard M. of Sherman Brothers fame), adapted by Oscar Hammerstein II and Dorothy Yost from Irene Castle’s stories “My Husband” and “My Memories of Vernon Castle.”

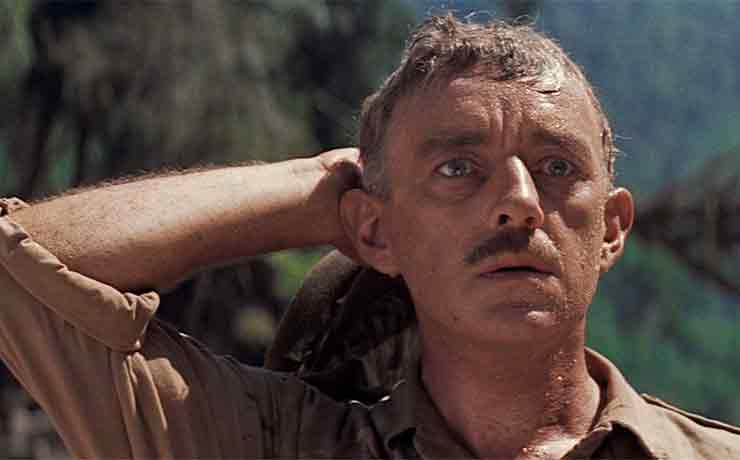

Mistaken Identity? Hardly, since they’re playing historical figures in a film based on firsthand accounts. Irene (née Foote) is also credited with designing Ginger’s costumes, although she (Irene) reportedly hated them, and serving as technical advisor, although she reportedly battled with director H.C. Potter over its historical accuracy (or lack thereof). The two meet in 1911, when Vernon is a vaudeville “second comic” specializing in rich drunks (above) and Irene is an aspiring entertainer living with her parents in New Rochelle. She urges him to play to his strengths as a dancer, leading to a partnership both professional and personal. What would normally be the end of an F&G movie, as they declare their love and wed, is achieved pleasantly early, and their rise to fame is a rapid one. When World War I breaks out, British-born Vernon is moved to join the Royal Flying Corps (below), yet in a bitter irony, after surviving combat (the film doesn’t mention it, but he won the Croix de Guerre), he sacrifices his life in 1918 to avoid a collision on a training flight.

Other Colorful Characters: Even—or perhaps especially—in black and white, nobody is more colorful than Walter Brennan, who plays the Foote family retainer, conveniently named Walter…and, in real life, black, dumbfounding La Castle. Brennan was one of only three male actors to win as many Oscars, all for Best Supporting Actor: Come and Get It (1936), Kentucky (1938), and The Westerner (1940); for those who, per the great John Frankenheimer, “put a lot of stock in these…things,” he was nominated in the same capacity for a film I know better, Howard Hawks’s Sergeant York (1941). Brennan was also memorable as Old Man Clanton in Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1946), but in my mind he will always be indelibly etched as Eddie (“Was you ever bit by a dead bee?”) in another of his Hawks films, To Have and Have Not (1944, below). Even more so, I associate Edna May Oliver with a single role, that of the formidable Miss Pross in A Tale of Two Cities (1935), although she had a distinguished career, including another of David O. Selznick’s Dickens adaptations that same year, David Copperfield. Nominated as Best Supporting Actress for Ford’s Drums along the Mohawk (1939), she originated the role of Stuart Palmer’s amateur sleuth, Hildegarde Withers, in The Penguin Pool Murder (1932) and two sequels, and here plays the Castles’ imperious agent, Maggie Sutton.

Usual Suspects: Largely unsung (ha ha) series vet Yost is finally credited for the first time since The Gay Divorcee. With her reported focus on racial minorities, she may have shared Irene’s chagrin at the, uh, whitewashing of Walter Ashe. Interestingly, per their Wikipedia entry, on which I have drawn heavily for background, the real-life Castles (below) “traveled with a black orchestra…and had an openly lesbian manager, Elisabeth Marbury.”

Immortal Number(s): None introduced here, for obvious reasons, but the score is laced with whole or partial renditions of such beloved standbys as “Moonlight Bay,” “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” “By the Beautiful Sea,” “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” and “Little Brown Jug.” I believe the only new number, sung by Fred and danced by the translucent Castles (Vernon being dead and all) at the teary fadeout, was “Only When You’re in My Arms.” It was written by Con Conrad, who’d contributed two fine tunes to TGD, and the famous team of composer Harry Ruby and lyricist Bert Kalmar, respectively played in the biopic Three Little Words (1950) by Red Skelton and…some dude named Astaire.

Bonkers Number(s): Believing Vernon to be an influential showbiz figure when they meet (the closest we get to mistaken identity), Irene tries to impress him by recreating, in the family’s parlor, Bessie McCoy’s rendition of “The Yama Yama Man,” her signature Broadway hit from Three Twins (1908). The sight of Ginger (above) cavorting in her black satin Pierrot clown suit, with floppy-fingered gloves that make her look like a cross between Marvel’s Beetle and Nosferatu, can best be described as outré. Of interest to my friend Fred, Wikipedia reports that the appearance of Max Fleischer’s Koko the Clown is based on this, and “a 1922 sheet music drawing makes the connection explicit, saying ‘Out of the Inkwell, the New Yama Yama Clown.’” Incredibly, it is also the title track of a 1967 album by the dreaded George Segal, and I can’t resist another Wiki quote: “In Warner’s Look for the Silver Lining (1949) [a biopic of Marilyn Miller], June Haver plays…Miller imitating Ginger Rogers imitating Irene Foote imitating Bessie McCoy’s performance.”

New Dance Craze Allegedly Sweeping the Nation: Basically the object of the exercise. The Castles, again per their Wikipedia page, “helped remove the stigma of vulgarity from close dancing”; in addition to introducing their “Castle Walk,” they popularized ragtime, jazz, and such steps as the foxtrot and the tango. Irene, in particular, was a trendsetter in numerous ways, e.g., with her trademark bob hairdo and as a fashion icon and designer, although she was not that Irene, as in “Gowns by,” who got an early break designing for Ginger in SWD. Irene outlived Vernon—with whom she is interred—by half a century, remarried three times, and was an animal-rights activist (cue cheers from Madame BOF).

White Tie and Tails? Yes, starting with the impromptu audition Maggie arranges at the Café de Paris, debuting the “Castle Walk” to “Très Moutarde” (Too Much Mustard).

Unique Aspect(s): Only fact-based entry, unhappy ending (perhaps explaining its undeserved box-office failure), and series credit for Potter—who directed Fred in Second Chorus (1940) and Cary Grant in Mr. Lucky (1943) and Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948)—or Hammerstein (yes, as in “Rodgers and”).

Title: The Barkleys of Broadway (1949).

Based on Stageplay? Nope; original screenplay by Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

Mistaken Identity? Again, hardly. The Barkleys go the Castles one better, already successful spouses when the curtain goes up—literally. The credits are superimposed over them dancing to “Swing Trot” from their latest hit show, written by composer Ezra Millar (Oscar Levant) and lyricist/director Josh (Fred), who co-stars with Dinah (Ginger). The metacinematic plot mechanism is that she bridles over frequent comparisons of Josh to Svengali and yearns to be a serious actress, especially when pompous playwright Jacques Pierre Barredout (Jacques Francois) opines that she’d be perfect for his opus The Young Sarah…as in Bernhardt. Things duly, albeit temporarily, head south from there.

Other Colorful Characters: Levant (above) certainly qualifies, with his basset-hound face and the mordant wit on display in the “Weekend in the Country” trio, not to be confused with Stephen Sondheim’s eponymous and similar song from his Bergman-based A Little Night Music (1973). He was, among many things, an expert concert pianist, so we’re treated to renditions of Khachaturyan’s “Sabre Dance,” banged out at a dinner party in response to requests from nobody but himself, and Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, played at the Mercy Hospital benefit to which he lures the on-the-outs Barkleys. I can’t hear the former without thinking of the Simpsons episode where Itchy, performing it in one of their distressingly sadistic cartoons, throws a hockey player in full Buffalo Sabres regalia at Scratchy; the latter, popularized as the theme to Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre on the Air, is heard on his notorious War of the Worlds Halloween broadcast. I’m sure there are those who consider Billie Burke, best known as Glinda the Good Witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz (1939), adorable, but I just find her insufferable as a ditzy socialite.

Usual Suspects: Not many, which is unsurprising given the film’s genesis. Replacing the injured Gene Kelly, Fred ended his first retirement to join Judy Garland in Easter Parade (1948), during the production of which MGM’s Arthur Freed had the legendary writing duo of Singin’ in the Rain (1952) start this screenplay. It was intended to re-team them with director Charles Walters, but when rehearsals proved that Judy was not up to it, Freed hit on the idea of reuniting F&G. As jarring as it is to see them ten years older (presumably ruling out the usual love-at-first-sight scenario), and in Technicolor rather than the sophisticated elegance of black and white, my qualified affection for the film is probably due as much as anything else to my being more of an RKO guy than an MGM guy. But Fred’s invaluable collaborator, Hermes Pan, is credited as dance director for “Wings on My Shoes” (see below), and Ira Gershwin returns as lyricist. Now bereft of George, he’s teamed here with Harry Warren, whose countless hits include the Oscar-winning “Lullaby of Broadway” and the BOF favorite “I Only Have Eyes for You.”

Immortal Number(s): Significantly, the only one is the Gershwins’ “They Can’t Take That Away from Me,” repurposed from SWD in a rare example of Astaire recycling a song. At least it’s given a new twist, since they grudgingly dance to it together at the benefit (Oh, you tricky Ezra!), whereas before it was merely Fred’s vocal. Sadly, Harry and Ira really don’t strike gold with any of their new songs, which include a broadly comedic faux-Scottish duet, complete with kilts, “My One and Only Highland Fling” (below).

Bonkers Number(s): “WOMS” is another gimmick-number for Fred—e.g., dancing on the ceiling in MGM’s Royal Wedding (1951)—in which he plays a shoe-shop proprietor dancing, via special effects by Irving G. Ries, with disembodied footwear. I must confess that I have two curmudgeonly kvetches. First, while my suspension of disbelief might let me accept a fantasy sequence in such a film, it is specifically presented as part of Josh’s stage performance, so how are we supposed to think he achieved that? Second, at the end, he trashes the shop and, presumably, his own livelihood. Again, hard to swallow.

New Dance Craze Allegedly Sweeping the Nation: No.

White Tie and Tails? Yes, at the benefit (below), natch.

Unique Aspect(s): Plenty. F&G’s only color or MGM collaboration; only series entry for Walters or the uncredited Sidney Sheldon, who scripted Easter Parade with It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) alumni Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett (they were married, unlike the purely professional partnership of Comden and Green). An Oscar-winner for The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer (1947), future bestselling novelist Sheldon also later created such hit series as The Patty Duke Show, I Dream of Jeannie, and Hart to Hart. The film’s cinematography earned its sole Oscar nomination, one of a whopping fourteen over 26 years for Harry Stradling, Sr., who specialized in musicals but won for both The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) and My Fair Lady (1964). Now that’s what I call range!

.jpg)